Ever wonder why your prescription for metformin costs $5, but the brand-name version costs $150-even though they’re the same thing? It’s not a pricing glitch. It’s the result of a quiet, complex system insurers use to decide which generic drugs get covered, and which ones don’t. This system doesn’t just affect diabetes meds. It shapes what you pay for antibiotics, blood pressure pills, antidepressants, and more. And if you’ve ever been denied a drug or switched to a generic that didn’t work, you’ve felt its impact firsthand.

How Insurers Pick Which Generics to Cover

Insurance companies don’t just pick generics randomly. They rely on Pharmacy & Therapeutics (P&T) committees-groups of doctors, pharmacists, and health economists-who review drugs like a jury reviews evidence. These committees don’t meet in boardrooms with fancy titles. They work from data: clinical studies, real-world outcomes, safety reports, and cost numbers.

To even be considered, a generic drug must be approved by the FDA. That means it has the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand-name drug. But approval isn’t enough. The P&T committee asks: Does it work as well? Is it safe? And is it cheaper?

Here’s the key: if two generics do the same job, the cheaper one wins. That’s not greed-it’s how the system is designed to save money. Medicare Part D plans saved $141 billion in 2019 just by using generics instead of brand-name drugs. That’s money that keeps premiums lower for everyone.

The Tiered Formulary System Explained

Most insurance plans use a tiered system to organize drugs. Think of it like a pricing ladder. The lower the tier, the less you pay.

- Tier 1: Preferred generics-usually $0 to $15 for a 30-day supply.

- Tier 2: Non-preferred generics or low-cost brands-$20 to $40.

- Tier 3: Brand-name drugs without generic equivalents-$40 to $100+.

- Tier 4: Specialty drugs-often $100 to $500+.

Over 92% of Medicare Part D plans put all generics in Tier 1. That’s not an accident. It’s policy. Insurers know generics cost 80-85% less than brand-name drugs. So they push them to the bottom tier-where patients are most likely to choose them.

But here’s the catch: not all generics are treated the same. Even within Tier 1, some are labeled “preferred.” That means the insurer has negotiated a better price with that manufacturer. If you get a non-preferred generic, you might pay $15 instead of $5. It’s the same drug, same effectiveness-but different cost to you.

What Factors Really Matter to Insurers?

Insurers don’t just look at price. They look at three things:

- Clinical Effectiveness: Does the drug actually help people? P&T committees dig into peer-reviewed studies, real-world data, and outcomes from patient registries. A drug that reduces hospital visits for heart failure gets priority over one that just lowers a lab number.

- Safety: Has it caused side effects? Are there black box warnings? A generic with a history of allergic reactions or dangerous interactions gets flagged-even if it’s cheap.

- Coverage Consistency: If a drug is already widely used and trusted, insurers keep it. Switching to a new generic means retraining pharmacists, updating systems, and dealing with patient complaints. Sometimes, the status quo is cheaper than change.

For example, if you’re on a generic version of lisinopril for high blood pressure, your insurer is unlikely to switch you-even if a newer generic hits the market. Why? Because it works. No need to fix what isn’t broken.

Why You Might Get Switched to a Different Generic

Here’s where things get messy. You might be prescribed one generic-say, levothyroxine from Teva-but your insurer’s formulary only covers the version made by Mylan. So the pharmacy gives you Mylan instead. That’s called therapeutic substitution.

78% of commercial plans allow this. Medicare Advantage plans do it less often-only 52% do. But here’s the problem: not all generics are identical. They have the same active ingredient, but different fillers, binders, and coatings. For most people, it doesn’t matter. For some-especially those with thyroid conditions, epilepsy, or kidney disease-it can.

A 2023 survey found 31% of patients reported side effects after being switched to a different generic. One man with hypothyroidism went from feeling fine on Teva to experiencing heart palpitations and fatigue after switching to Mylan. His doctor had to file an exception. It took five days. He got his original back-but only because he pushed.

What to Do If Your Drug Isn’t Covered

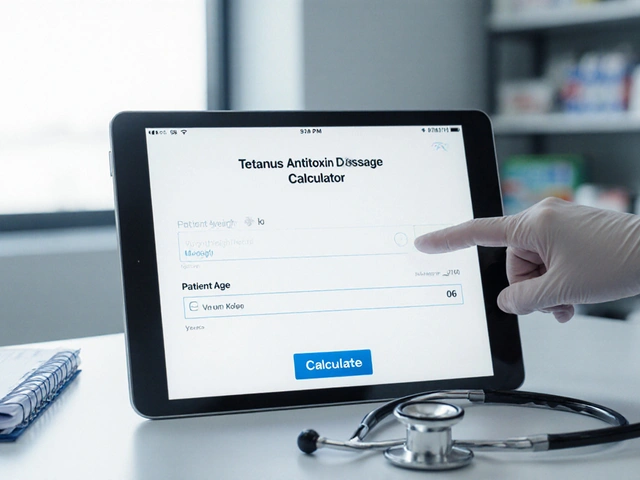

If your prescription isn’t on the formulary, you’re not stuck. You can appeal.

The process is simple:

- Ask your doctor to write a letter explaining why the generic you need is medically necessary-for example, “Patient experienced adverse reaction to Formulary Generic A, responded well to Brand B.”

- Submit the request through your insurer’s portal or fax.

- Insurers must respond in 3 business days. If it’s urgent-like a life-threatening condition-they have 24 hours.

- If they don’t respond? The request is automatically approved.

43% of patients get denied at first. But 78% get coverage after appealing. That’s not luck. That’s the system working as intended.

Still, it’s exhausting. Physicians spend an average of 13.3 hours a week just handling prior authorizations and formulary exceptions. Many say it feels like navigating a maze with no map.

What’s Changing in 2025?

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 capped out-of-pocket drug costs for Medicare Part D at $2,000 per year-starting in 2025. That’s good news for patients. But it’s forcing insurers to rethink their strategies.

Now, instead of pushing expensive brand-name drugs with high rebates, insurers are doubling down on high-volume generics. Why? Because if patients aren’t paying more than $2,000 a year, insurers need to control costs upstream. That means even more pressure on P&T committees to pick the cheapest, safest, most effective generics.

At the same time, the FDA is speeding up approvals for complex generics-like inhalers, insulins, and injectables. That means more options will hit the market. But it also means more choices for insurers to sort through.

And then there’s the elephant in the room: drug shortages. As of October 2023, 372 drugs were in short supply in the U.S. Seventy-eight percent of them were generics. If your insurer’s preferred generic runs out, you might be stuck with a more expensive alternative-unless you appeal.

What Patients Should Know

You don’t need to be a pharmacist to understand how this works. Here’s what you can do:

- Check your plan’s formulary before you fill a prescription. Most insurers have online tools.

- Ask your pharmacist: “Is this the preferred generic?” If not, ask if they can switch it.

- If you notice side effects after a switch, tell your doctor immediately. Document it.

- Don’t assume your insurer will automatically cover the same generic next year. Formularies change.

And remember: just because a drug is generic doesn’t mean it’s not important. It’s often the only reason you can afford to stay on your medication.

Why This Matters for Chronic Conditions

For people with diabetes, high blood pressure, or high cholesterol, daily meds aren’t optional. They’re life support. If you can’t afford your pill, you skip it. And that leads to ER visits, hospitalizations, and worse outcomes.

Insurers know this. That’s why they push generics so hard. They’re not trying to be cruel. They’re trying to keep the whole system from collapsing. But the system has cracks. Patients get caught in them. Doctors get burned out. Pharmacists are caught in the middle.

The real win? When a patient gets the right drug at the right price-and doesn’t have to fight for it.

Why do insurers cover some generics but not others?

Insurers cover generics based on cost, safety, and effectiveness. Even if two generics are FDA-approved, one might be cheaper because the manufacturer negotiated a better deal. Insurers favor those to save money. They also avoid generics with known safety issues or poor patient outcomes.

Can I ask my doctor to prescribe a specific generic?

Yes. You can ask your doctor to write “Dispense as Written” or “Do Not Substitute” on your prescription. That tells the pharmacy to give you the exact brand or generic your doctor chose. But your insurer might still require prior authorization or higher cost-sharing.

What’s the difference between preferred and non-preferred generics?

Preferred generics are the ones your insurer has negotiated the lowest price for. Non-preferred generics are still covered, but cost more. They’re the same drug-just made by a different company that didn’t get the best deal. You pay more, but you still get the medication.

Why was my generic switched without warning?

Insurers can change their formularies at any time. If they negotiate a better price with another manufacturer, they’ll switch. You might not be notified unless you check your plan’s formulary updates. Always ask your pharmacist if your generic changed.

Do all insurance plans cover the same generics?

No. Medicare Part D, Medicaid, and private insurers each have their own formularies. A generic covered by UnitedHealthcare might not be covered by Blue Cross. Always check your specific plan’s list before filling a prescription.

How long does an exception request take?

Standard requests are reviewed within 3 business days. If it’s urgent-like you’re running out of medication or having side effects-the insurer must respond in 24 hours. If they don’t respond, your request is automatically approved.

What Comes Next?

The future of generic coverage isn’t just about price. It’s about precision. As AI and personalized medicine grow, we’ll see generics tailored to specific genetic profiles. Will insurers cover them? Probably-if they’re proven to reduce hospital stays. But right now, the system is built for volume, not individual needs.

For now, your best move? Know your plan. Ask questions. Keep records. And don’t be afraid to appeal. The system isn’t perfect-but it works better when you use it.

Shubham Semwal

Bro, this whole system is a scam. Generics are the same drug, period. If you're paying $15 for a pill that should cost $2, you're being robbed. Insurers aren't saving money-they're just shifting the burden to patients while their execs buy yachts. Wake up.

Kaleigh Scroger

Look, I’ve been on a dozen different generics over the years-metformin, lisinopril, levothyroxine-and I can tell you the differences aren’t always in the active ingredient. Sometimes it’s the fillers. I had a patient once who went from feeling fine to having full-on panic attacks after switching from one generic levothyroxine to another. Same dose. Same manufacturer. Different binder. Turns out she was allergic to the corn starch in the new version. No one told her. No one checked. And the pharmacy just shrugged. That’s not healthcare. That’s roulette with your life. I’ve seen this too many times. Doctors don’t have time to track every formulation change. Pharmacists are overworked. Patients are left guessing. And insurers? They don’t care as long as the cost per script drops. It’s not about safety. It’s about the bottom line. And when you’re the one with the heart palpitations or the seizure risk or the thyroid crash? You’re just a line item. We need mandatory reporting of adverse events tied to generic switches. Not optional. Mandatory. And we need transparency-like a public database showing which fillers are in which version. Otherwise, we’re just playing Russian roulette with people’s health. And it’s not fair. It’s not ethical. And it’s not medicine.

Cecily Bogsprocket

I get why insurers do it. I really do. My mom’s on six meds. Without generics, she couldn’t afford any of them. But I also remember the month she switched from one generic omeprazole to another and spent three days in bed with nausea so bad she couldn’t keep water down. It wasn’t the drug-it was the coating. The one she’d been on for five years had a slow-release shell that didn’t irritate her stomach. The new one? Powdered filler. Same FDA stamp. Different experience. It’s not about greed. It’s about how we treat people as numbers instead of bodies. And we’re all just one bad switch away from being the person who gets caught in the cracks.

archana das

In India, we don’t have this problem. Generics are cheap because the government controls pricing. No tiers. No preferred brands. Just medicine. People take them daily without fear. I wish the U.S. could learn that health isn’t a market-it’s a right. You shouldn’t need to appeal just to breathe.

Jonah Thunderbolt

OMG I literally cried reading this 😭💔 I’ve been on the same generic for 8 years and they switched me last month and now I’m having night sweats and I didn’t even know it was the drug??!!?? My doctor just said "it’s the same thing" but it’s NOT THE SAME THING I’M SUFFERING 😭😭😭 someone please help me??!!

Gayle Jenkins

Don’t let them silence you. If you’re having side effects after a switch, document everything-date, symptoms, pharmacy, drug name. Then go to your doctor and say "I need a prior auth for the original version." If they say no, escalate. Call your insurer’s member services. Ask for a case manager. If they still refuse, file a formal complaint with your state’s insurance commissioner. You’re not being difficult. You’re being smart. And you’re not alone. I’ve helped over 20 people get their original meds back. It’s a process. It’s exhausting. But it works.

Elizabeth Choi

Let’s be real. The 31% of patients reporting side effects after a switch? Most of them are just paranoid. If the FDA approved it, it’s safe. People need to stop overreacting to minor changes. It’s not like the drug is being replaced with sugar pills. It’s the same molecule. Get over it.

Savakrit Singh

It is a matter of regulatory arbitrage. The United States permits a variance in bioequivalence thresholds that is significantly higher than the European Union's standard. Consequently, the pharmacokinetic profiles of generics approved in the U.S. may exhibit greater inter-individual variability. This is not a failure of the system-it is a structural feature. The FDA's current paradigm prioritizes cost-efficiency over pharmacological precision. This is not a critique of the FDA per se, but rather a reflection of broader economic policy decisions that have been externalized onto the patient population.

Mira Adam

Insurers don’t care about you. They care about profit margins. The fact that you have to appeal for a drug that’s been on the market for 20 years is proof that the system is broken. And no, your doctor can’t fix it. They’re just another cog in the machine. You think they want to spend 13 hours a week on paperwork? They don’t. But they’re forced to. Because the system rewards bureaucracy over care. And the worst part? You’re supposed to be grateful you get anything at all.

Miriam Lohrum

It’s strange how we treat medicine like a commodity. We accept that a pill can be swapped out like a brand of cereal. But your body doesn’t care about contracts or rebates. It reacts to what’s in it. Maybe we need to stop thinking of drugs as products and start thinking of them as part of a person’s life. What if we treated prescriptions like prescriptions for oxygen? You wouldn’t swap out the oxygen tank because another one was cheaper. You’d make sure it worked.

Alex Hess

Wow. So the system is rigged. Shocking. Next you’ll tell me that rich people get better care. Who knew? I’m just glad I don’t need these drugs. Maybe if you spent less time on meds and more time working, you wouldn’t need them in the first place. Just saying.

Kaleigh Scroger

And this is why I keep a binder. Every time I switch, I write down the pill color, shape, imprint, manufacturer, and pharmacy. I’ve got a photo of each version. When I had the reaction last year, I brought it to my doctor. She said, "I’ve never seen this before." But I had. And I showed her. She called the insurer. They switched me back. Don’t wait until you’re in crisis. Document everything. Knowledge is power. And if you’re lucky enough to have a doctor who listens? Hold onto them. They’re rare.