When you fill a prescription, you might not notice the switch from a brand-name drug to a generic version. But behind the scenes, a complex system of insurance rules, state laws, and pharmacy practices is deciding what you get-and how much you pay. Generic substitution isn’t just about saving money. It’s a legal and medical balancing act between cost control, patient safety, and physician authority. If you’ve ever been handed a different pill than what your doctor prescribed, or got hit with a surprise bill because your insurer refused to cover the brand, you’ve felt the friction in this system.

What Generic Substitution Really Means

Generic substitution happens when a pharmacist swaps a brand-name drug for a chemically identical generic version. It’s not random. The FDA requires generics to have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand. More importantly, they must prove bioequivalence: the body absorbs the generic at the same rate and to the same extent as the brand. For most drugs, that means the generic’s absorption (measured as AUC and Cmax) must fall within 80% to 125% of the brand’s. That’s not a guess-it’s science. And it’s why 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. are now generics, even though they make up only 18% of total drug spending.

But here’s the catch: bioequivalence doesn’t always mean identical experience. Some patients report side effects, reduced effectiveness, or allergic reactions when switching, even with FDA-approved generics. Why? Because generics can differ in inactive ingredients-fillers, dyes, preservatives. For someone with a sensitivity to corn starch or a specific dye, that difference can be real. That’s why the FDA still says generics are safe for nearly all patients, but doctors and pharmacists know exceptions exist.

How Insurance Companies Drive Substitution

Insurance companies don’t just allow substitution-they push it. Their business model depends on lowering drug costs, and generics are the easiest win. Many private insurers, like Sun Life Financial and Great West Life in Canada, have mandatory substitution policies. If you’re prescribed a brand-name drug, they’ll only pay for the generic version. If you insist on the brand, you pay the difference out of pocket. In one 2013 report, the average brand-name claim was $72, while the generic was $27-a 62.5% drop. That’s money saved for the insurer and, in theory, for you.

But it’s not always that simple. Some insurers use formulary restrictions to force switches. They remove a brand-name drug from their approved list entirely. If your doctor prescribes it, the pharmacy won’t even try to fill it unless you or your doctor jump through hoops. That’s called non-medical switching. No new diagnosis. No worsening symptoms. Just a policy change. And it’s common. Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) like Express Scripts and OptumRx control 85% of these decisions. They decide which drugs get covered, and which don’t.

State Laws Vary Wildly

Insurance rules aren’t the whole story. Each state has its own laws about who can substitute and under what conditions. In 19 states, pharmacists are required to substitute generics unless told otherwise. In 7 states and Washington, D.C., they must get your explicit consent before swapping. In 31 states, they have to notify you after the fact-sometimes with a sticker on the bottle, sometimes with a phone call.

Texas gives a clear example. Under Texas Administrative Code § 309.3, three conditions must be met for substitution:

- The generic must cost you less than the brand.

- You haven’t refused substitution.

- Your doctor didn’t write "Dispense as Written" or "Brand Medically Necessary" on the prescription.

If any of those three aren’t true, substitution is illegal. That’s why your doctor’s handwriting on the prescription matters more than you think. A single phrase can block a switch.

When Brand-Name Drugs Are Necessary

Not all drugs are equal when it comes to substitution. Some, like warfarin, lithium, and certain anti-seizure medications, have a narrow therapeutic index. That means the difference between a helpful dose and a dangerous one is tiny. Even small changes in absorption can cause problems. The FDA says approved generics are safe for these drugs too. But real-world experience tells a different story.

Reddit user u/MedPatient87 switched from Synthroid (brand) to generic levothyroxine after their insurer forced the change. Their thyroid levels went haywire. Three dose adjustments over six months. That’s not rare. A 2022 review of 1,247 patient complaints on Drugs.com found 37% involved substitution despite "Dispense as Written" instructions. The fix? Your doctor must clearly state medical necessity.

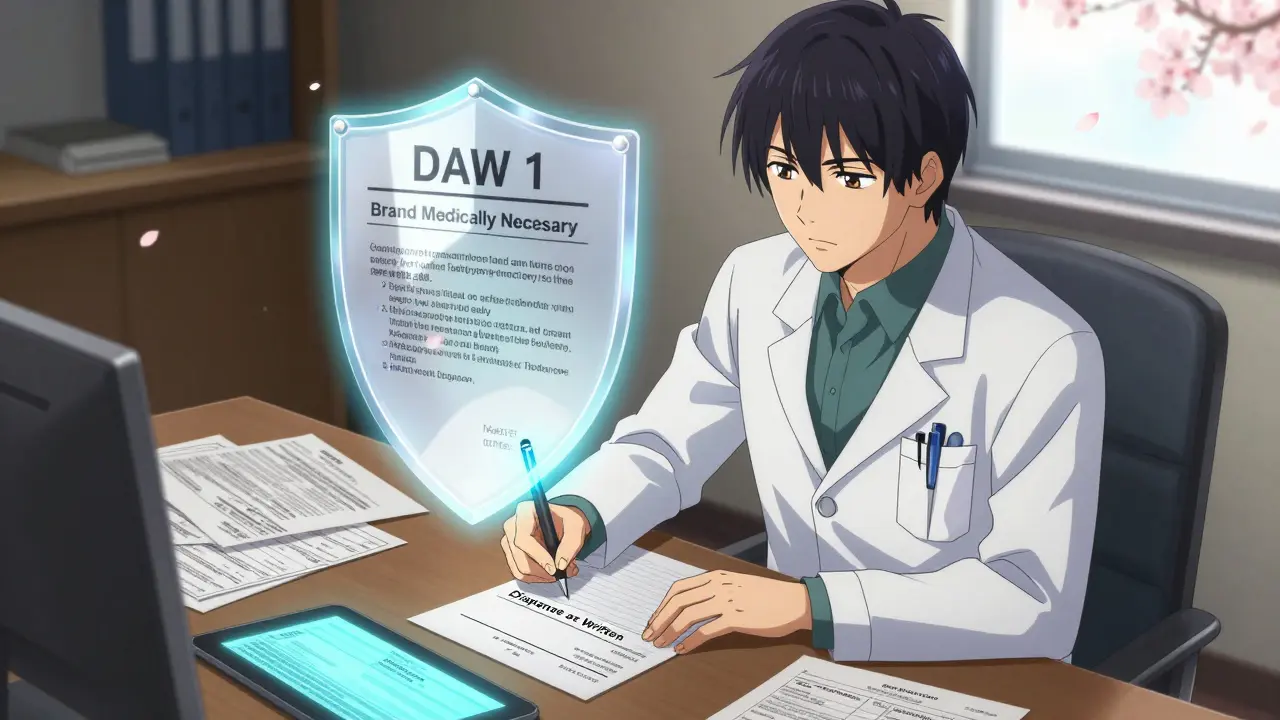

Most insurers accept one of two phrases on the prescription:

- "Dispense as Written" (DAW 1)

- "Brand Medically Necessary"

That’s your legal shield. If your doctor writes it, the pharmacy can’t substitute-even if your insurance wants to. In states like Texas, it’s legally binding. In others, it’s still the strongest argument you have.

Getting Your Brand-Name Drug Approved

Even with "Dispense as Written," your insurer might still deny coverage. That’s when prior authorization kicks in. This isn’t a formality. It’s a process.

For example, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan requires physicians to submit:

- Proof of therapeutic failure with a generic (lab results, symptom logs)

- ICD-10 diagnosis codes matching the condition

- A statement explaining why the brand is medically necessary

They approve 78% of these requests when properly documented. But the rules change between insurers. Aetna might ask for three clinical criteria. UnitedHealthcare might need five. Your doctor’s office may not know the difference. That’s why patients often get stuck.

Here’s how to navigate it:

- Ask your doctor to write "Dispense as Written" or "Brand Medically Necessary" on the prescription.

- Call your pharmacy and ask if they’ve received prior authorization from your insurer.

- If denied, ask your doctor to submit documentation-be specific about why the generic didn’t work.

The whole process can take 2 to 14 business days. Don’t wait until your prescription runs out. Start early.

The Biosimilar Challenge

For biologic drugs-like Humira, Enbrel, or insulin analogs-the rules are even tougher. These aren’t simple chemicals. They’re complex proteins made from living cells. A generic version isn’t called a "generic"-it’s a "biosimilar." And the FDA requires more testing to prove similarity. Even then, 45 states have extra rules: mandatory prescriber notification, patient consent, or both.

As of 2023, only 38 biosimilars had been approved in the U.S. compared to over 10,000 small-molecule generics. That’s because the science is harder. And insurers are slower to adopt them. If you’re on a biologic, substitution is less likely. But if it happens, you should be notified in writing within 5 business days. That’s federal law under the CARES Act.

What You Can Do

Generic substitution is here to stay. It saves billions. But it’s not foolproof. You have rights. Here’s what to remember:

- Always check your prescription label. If the drug name changed, ask why.

- If your doctor didn’t write "Dispense as Written," they might not know substitution is happening.

- Keep a log of symptoms after a switch. If you feel worse, document it.

- Call your insurer. Ask: "Is this drug on my formulary? If not, how do I get an exception?"

- Don’t assume generics are always cheaper. Sometimes the brand is on sale, and the generic isn’t covered.

Most patients save money with generics. But if you’re one of the few who doesn’t, you’re not imagining it. You’re dealing with a system designed for efficiency-not individual experience. Knowing your rights, your doctor’s role, and your insurer’s rules gives you control.

Can my pharmacist substitute my brand-name drug without telling me?

It depends on your state. In 19 states, pharmacists are required to substitute unless told otherwise. In 7 states and Washington, D.C., they must get your consent first. In 31 states, they must notify you after the fact-usually with a label or receipt. Always check your prescription bottle and receipt. If the name changed and you weren’t told, ask the pharmacy.

What if my doctor says "Dispense as Written" but my insurance still denies coverage?

If your doctor wrote "Dispense as Written" or "Brand Medically Necessary," the pharmacy must fill it as written. But your insurance might still refuse to pay. That’s when you need prior authorization. Your doctor must submit documentation proving the brand is necessary-like lab results showing the generic didn’t work. If they don’t, call your insurer’s customer service and ask for the appeals process. You have the right to challenge a denial.

Are generic drugs really as effective as brand-name drugs?

For most people, yes. The FDA requires generics to prove bioequivalence-meaning they work the same way in the body. Studies show no difference in effectiveness for 90% of drugs. But for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin or epilepsy meds-some patients report changes in symptoms or side effects after switching. This isn’t because the active ingredient is different, but because of inactive ingredients or manufacturing differences. If you notice a change, tell your doctor and pharmacist.

Why do some generics cost more than the brand?

It’s rare, but it happens. Insurance formularies sometimes list a brand-name drug as preferred if it’s on a discount deal with the manufacturer. Meanwhile, the generic might not be covered at all-or it might be in a higher tier. Always compare your out-of-pocket cost at the pharmacy. The cheapest option isn’t always the generic.

Can I refuse a generic substitution even if my insurance requires it?

Yes. You can refuse any substitution, even if your insurer mandates it. If the pharmacist tries to switch your drug, you can say "No, I want the brand." You’ll pay more, but you’ll get what you asked for. Your right to choose your medication overrides insurance rules. Just be prepared to cover the difference.

What Comes Next

The push for generics isn’t slowing down. Medicare Part D now sees 94% generic substitution rates. PBMs are expanding their formularies. States are tightening rules on biosimilars. But the system is still messy. Patients, doctors, and pharmacists are caught in the middle. The best defense? Stay informed. Know your prescription. Ask questions. Document changes. And don’t be afraid to push back when your health is at stake.

Anil bhardwaj

Been there. Got the generic levothyroxine, felt like a zombie for three weeks. Went back to brand, back to normal. Insurance didn’t care. Docs don’t always know the difference between a filler and a felony. Just sayin’.

lela izzani

As a pharmacist, I see this every day. The system’s broken, but not because generics are bad. It’s because we’re treated like vending machines. Patients get swapped without context, and we’re stuck between legal liability and ethics. Always ask for the DAW code. It’s your power.

John Smith

Oh wow a whole essay on pills. Did you also write a 5000 word treatise on why your socks match? The FDA says it’s fine so shut up. You’re not special. Your thyroid doesn’t need a Nobel Prize.

Natanya Green

OMG I CAN’T BELIEVE THIS IS HAPPENING TO ME TOO!!! I switched to generic and I felt like I was being slowly drained by a vampire?? I cried for 47 minutes straight. My cat even noticed. I called my senator. I started a petition. I wore a t-shirt that said ‘I MISS MY BRAND’!!

Steven Pam

Love this breakdown. Seriously. It’s wild how much power we hand over without even knowing. But here’s the good news-you’re not powerless. You’ve got a voice, a doctor, and a pharmacy counter. Start with ‘Dispense as Written.’ That’s your first win. Then track your symptoms. Then call your insurer. Then repeat. You’re not just a claim number. You’re a human with a right to feel okay. Keep pushing. You got this.

Timothy Haroutunian

I read the whole thing and honestly I’m just tired. This whole system is a circus. Doctors write stuff. Pharmacies do stuff. Insurers do stuff. Patients get confused. And somehow we all pretend this is efficient. It’s not. It’s a mess. And nobody’s fixing it. So I just pay out of pocket now. It’s cheaper than my sanity. Also I hate formularies. They’re like a spreadsheet made by someone who hates people.

Erin Pinheiro

generic arent always better i mean like i had a friend who switched and she got like super dizzy and her hair fell out i think it was the dye or somethin? anyway doctors should just listen to patients not insurance companies. also why do they even have rules? just give us what we need. also i hate how they dont tell you until after. its like a surprise attack. and then you have to call like 5 people. ugh.

Michael FItzpatrick

Let me tell you something real: this isn’t about pills. It’s about who gets to decide your health. The system’s built to optimize profit, not people. And when you’re caught in that machine, you feel invisible. But here’s the secret-your doctor’s handwriting? That’s your rebellion. That scribble? That’s your armor. That phrase-‘Dispense as Written’? That’s your anthem. Don’t let them erase it. Don’t let them silence you. You’re not a cost center. You’re not a line item. You’re the reason this system exists. Fight for your right to feel like yourself. Every pill. Every dose. Every damn day.